As an integral part of our economy, the retail sector faces increased pressure to tackle climate change. But these decarbonisation efforts don’t come cheap. It’s going to take cooperative action and money — a lot of it. Who’s going to foot retail’s multi-trillion-dollar decarbonisation bill?

Climate change is real. So what?

The impacts of climate change are evident — from the torrential rainfalls in Pakistan last September that submerged a third of the country to the rising sea levels that will destroy entire habitats and engulf low-lying islands like Kiribati, an island located in the Pacific Ocean set to disappear by 2100. Closer to home, extreme weather patterns are a clear sign it’s time to start taking things seriously.

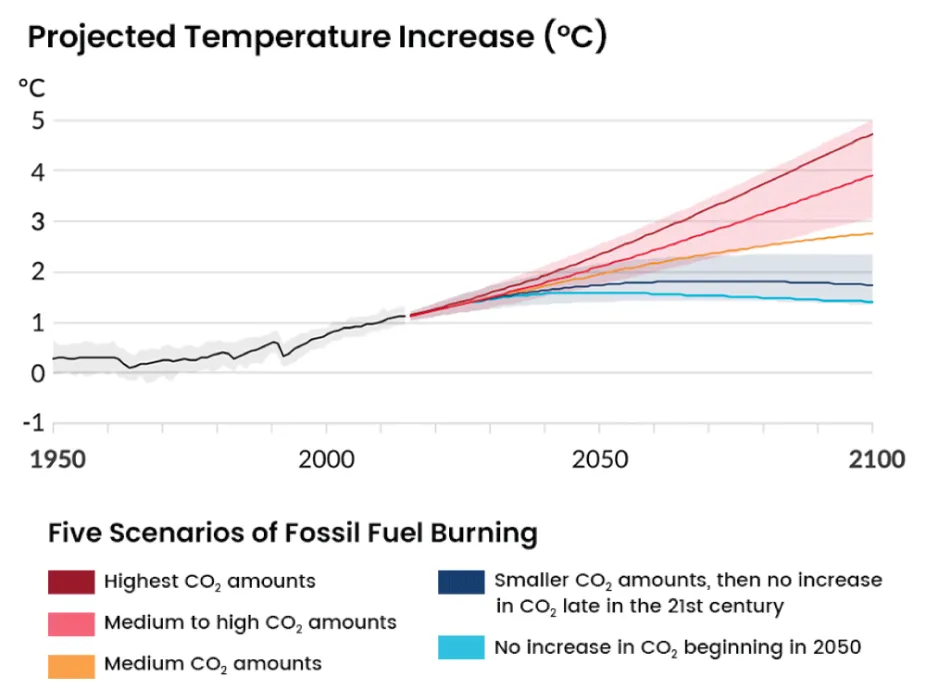

In a desperate attempt to combat this, world leaders have set an ambitious goal to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Yet, the efficacy of measures to reach this goal remain an unanswered question. Emissions are still soaring like there’s no tomorrow, and current simulations predict that the global average temperature will rise by up to 5°C by the end of the century if we continue down this trajectory (see Exhibit 1). A single degree has catastrophic impacts on our planet, let alone five.

Exhibit 1: Projected temperature increase based on the five possible scenarios of carbon emissions. Even if we reduce CO2 amounts to stop increasing after 2050, the global average temperature will still increase by 1-1.5°C — this is the best-case scenario (blue line in graph). If we emit CO2 at our current rate, the global average temperature will increase by 4.5-5°C (red line in graph). Image via the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Rebecca Henderson, John and Natty McArthur University Professor at Harvard Business School, says: “There’s not much sign governments are insisting those who emit greenhouse gasses should pay for the damage they cause… I think business should step up.”

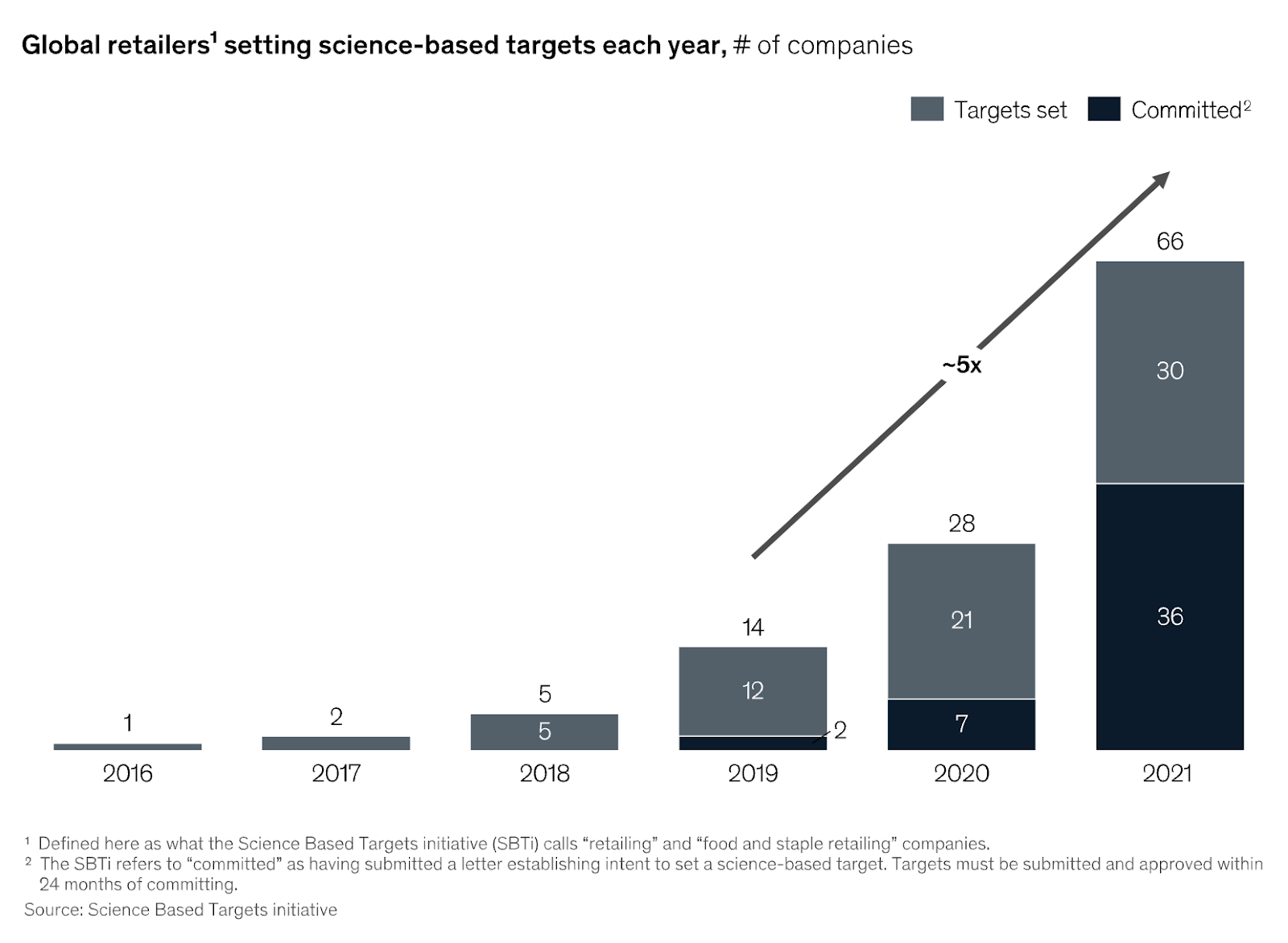

Past government action, businesses are poised to play a major role in decarbonisation efforts, and we have seen a proliferation of firms in the retail sector acting to do so. A recent report by McKinsey found that the number of retailers setting science-based emission targets increased fivefold between 2019 and 2021 (see Exhibit 2), with an increasing number of retailers jumping on the bandwagon, a clear sign that the private sector is starting to act.

Exhibit 2: In 2016, only one retailer set science-based emission targets, but that number has since increased to 66 in 2021, with the most significant increase between 2019 and 2021. Image via McKinsey & Company.

The big question: who will pay for decarbonisation?

These commitments don’t come for free. In totality, we expect net cost increases of about 20%, and funding requirements will be in the trillions. Investors are a critical piece to the puzzle and will play a dual role in our transition to a green economy.

For a start, investors are considering a firm’s ESG strategy as a fundamental component of their investment decisions, driven by pressure from LPs, lobbyists, and new ESG reporting standards. Effective January 1, 2024, the International Sustainability Standards Board will come into play, placing increased pressure on investors to evaluate firms based on these standards.

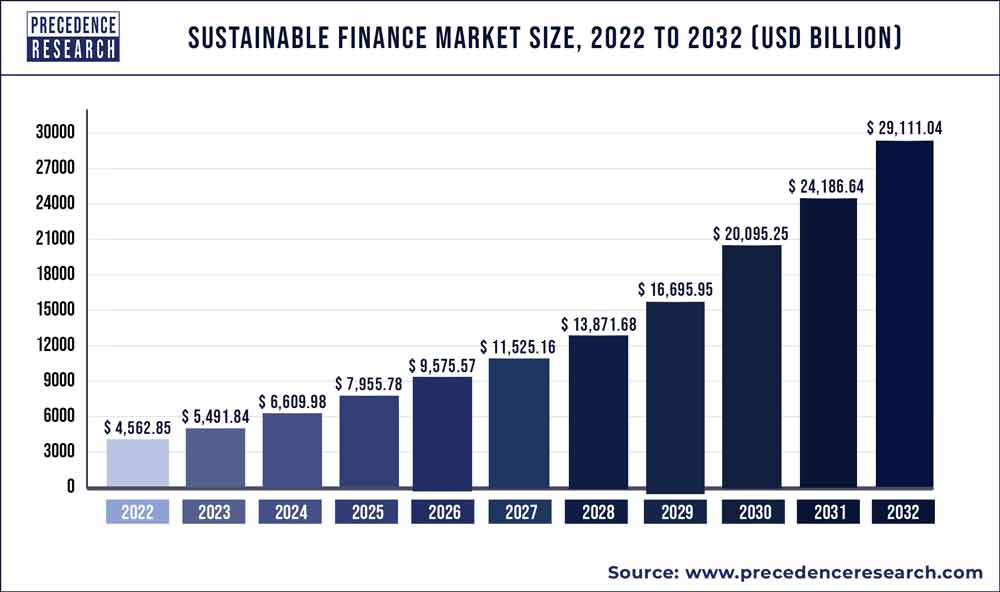

Blackrock CEO Larry Fink mandated firms to detail and report on their sustainability efforts in his most recent letter to CEOs of portfolio companies, and he is not alone. The global sustainable finance market is expected to increase sixfold in the next ten years (see Exhibit 3). This doesn’t come as a surprise, as we’ve seen both the emergence of green funds at incumbent investment firms like Vanguard’s Global Environmental Opportunities Stock Fund as well as the upsurge of new investors focusing on climate like 4WARD.VC.

Exhibit 3: The global sustainable finance market stood at USD $4.6T in 2022 and is expected to hit USD $29T by 2032, growing at a CAGR of 20.4% from 2023 to 2032. Image via Precedence Research.

In particular, investors prioritise purpose-driven firms and carbon footprint metrics when making investment decisions. The former involves a bias towards firms with a profit-with-purpose strategy, while the latter could include analysing common metrics like carbon emissions, energy and water usage, and waste diversion.

Patagonia is one such purpose-driven firm. It encourages customers to buy fewer items and repair older ones, catalysing the shift to a more sustainable future. Likewise, IKEA is promoting circular practices like furniture leasing as well as investing in renewable energy and sustainable sourcing in hopes of changing customer behaviour and achieving climate change by 2030.

Gen Z, the next generation of consumers, has proved to be environmentally conscious, with 72% saying they have already changed their behaviour to reduce their environmental impact. A study by Bain & Company found that over 70% of consumers are willing to pay more for products that positively impact the environment or health. This is especially prevalent in Asia Pacific, which took the lead, with over 90% of consumers willing to pay more, followed by European consumers at 74%, and American consumers trailing behind at 71%. Savvy investors have recognised this shift in consumer behaviour and are acting accordingly.

Moreover, investors favour firms with resilient and transparent supply chains. Emerging technologies play a pivotal role in accelerating the shift. For instance, AI algorithms that can forecast demand, enhance inventory management, and choose transportation routes that emit the least carbon have become increasingly prominent. In addition, the Internet of Things can regulate energy consumption within stores. Such uses are clear signposts of forward-thinking and adaptability — traits investors hunt for.

Aside from this, investors in both green debt and equity markets are willing to accept lower yields on bonds and pay premiums for stocks as they recognise the tremendous potential in low-carbon firms over longer investment horizons. This could effectively finance decarbonisation and smoothen the transition to a net zero economy.

Since 2016, Apple issued $4.7B in green bonds to support renewable energy initiatives, showcasing the company’s commitment to sustainability. This was well-received by investors. Another notable example is Tesla, which has skyrocketed in valuation over the past three years due to investors’ vision of a sustainable, electric-powered future. Many are paying huge premiums for its stock, expecting the transition to renewable energy to result in significant long-term returns.

What can retailers do on their own to curb emissions?

Reducing emissions across the value chain is a multifaceted issue requiring retailers to act individually and cooperatively with other stakeholders.

Individually, retailers could conduct research to understand customer sentiment and develop consumer-oriented green products. This requires substantial innovation, which often involves the acceptance of lower returns in the short-term for long-term gains. As such, retailers must push to set financial targets that will materialise over the long run.

Unilever’s Lipton Tea made the bold move to prioritise sustainable production when it partnered with the Kenyan Tea Development Agency and Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative to develop a “train the trainer” system. Under this initiative, lead farmers were trained on sustainable farming practices, before being tasked to train about 300 other farmers each.

This resulted in a hefty bill of over $10M, but by starting with purpose and committing to sustainability, sales and profits increased by $20M and $1.5M, respectively, in the same year — a feat in a close-to-commodity market. Though $1.5M doesn’t come close to the $10M invested, the alternative might have been to lose market share, risk reputational damage, or face uncertainty in its supply chain as conventional tea growing practices degrade the soil, lead to erosion, and pollute local water supplies. Additionally, these were just its first-year results, with the long-term story yet to be told.

Walmart, the largest retailer in the world by revenue, is another success story. In 2005, Sam Walton, its founder, committed to becoming 100% supplied by renewable energy, creating zero waste, and focusing on selling products that sustained both resources and the environment. People thought he was crazy when he did that, but just ten years after, Walmart eliminated 28.2 million metric tonnes of greenhouse gasses and doubled the fuel efficiency of its fleet, saving over $1B annually.

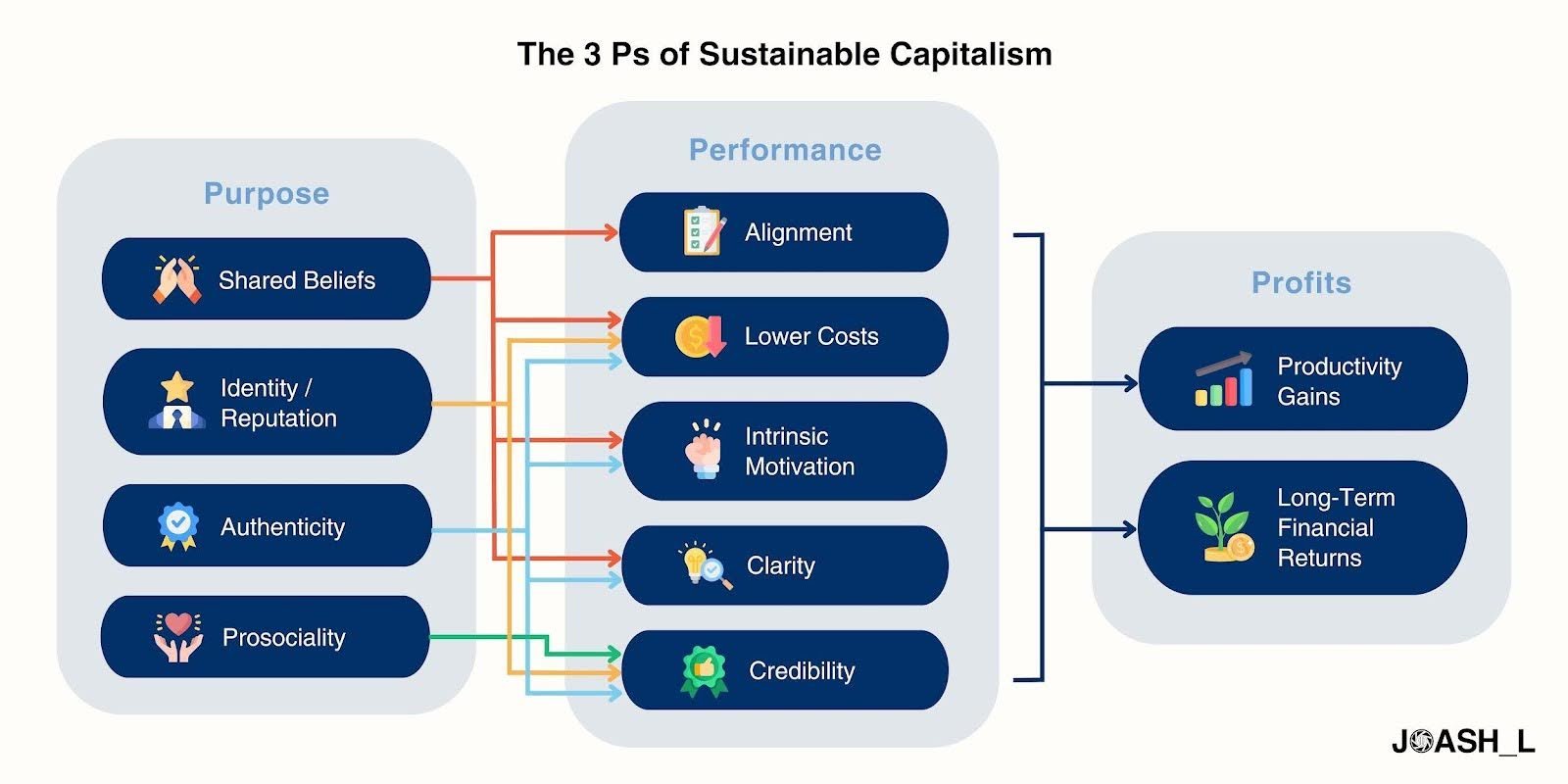

Unilever and Walmart are just two of many companies that have successfully adopted the profit-with-purpose framework, and extensive research in this sphere has revealed that profit improves performance, leading to long-term gains (see Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4: Ample research has shown that purpose-driven organisations perform better, in turn leading to greater profitability. The four dimensions of purpose drive performance through five mechanisms, with relationships mapped via the coloured arrows. Over the long run, performance fuels productivity gains and results in substantial financial returns. Image via JOASH_L.

Beyond this, retailers could create emission transparency at a product level. One way of doing so is to partner with vendors and form internal teams to develop emissions databases. With this data in hand, they can digitalise to make emissions information readily available to consumers.

Carrefour is investing in blockchain to trace textile products across their life cycle. This allows customers to use a QR code to see product-related information and track its carbon footprint, thereby allowing them to make well-informed purchase decisions.

On a multi-stakeholder level, retailers must engage in open dialogues with suppliers, industry associations, and governments. This is key as collaboration fosters a common understanding. Each stakeholder has different priorities and will therefore play a distinct role in decarbonisation efforts; retailers should expect varied interactions.

When interacting with industry associations, the goal is to set common standards on the distribution of decarbonisation costs within the industry to ease price negotiations with suppliers and drive industry-wide change. This helps smaller retailers by shouldering the cost of sustainable products, enabling them to offer competitive prices.

On the other hand, discussions with governments will revolve around policymaking and technologies that assist in decarbonisation. This entails communications to set attainable goals retailers can meet as an industry, knowledge sharing to implement low-carbon policies, and leadership in adopting decarbonisation technologies.

Case in point, Singapore’s Building Construction Authority funds research and development of mixed-mode ventilation systems and assists building owners in implementation. Such systems reduce energy usage and, thereby, carbon footprint.

F&N Foods and the National Environmental Agency also launched a joint initiative “Recycle N Save” in Singapore. This involved launching 50 reverse vending machines to encourage consumers to recycle plastic. Under the scheme, consumers who purchase pre-packaged drinks may have to fork out an additional 10 to 20 cents as a deposit and get this money back when they recycle their drinks. When the machines were first installed in March 2021, they received about 300 cans per day, but that number has since doubled.

The path forward: shifting mindsets

Funding retail’s decarbonisation bill is no easy feat. Though a concrete solution has yet to emerge, it’s clear that business as usual is not an option with changing consumer perceptions, increased LP pressure, and tightening government regulations.

While it remains a priority for retailers to develop robust decarbonisation plans, that’s only one part of the story. As we progress, a series of green opportunities will present itself, and multi-stakeholder cooperation is essential to capitalise on these emergences.

Investors are a vital stakeholder in this shift, with many reframing the question of investing in sustainability as a liability or nice-to-have, and instead, looking at it as an opportunity for long-term growth or a means to manage risks. In doing so, they have found a business case and effectively turned this challenge into an opportunity.

Editor’s Note: This is a deep-dive opinion editorial written by Joash Lee of VNTR Capital. The opinions in this commentary do not reflect our views and are solely his own.